School students find hundreds of potential new asteroids with PS1

January 20th, 2011 by willburgett Tags: Asteroid, classroom astronomy, outreach, pan-starrsOne of the many exciting aspects of being involved in the Pan-STARRS PS1 survey is the potential to utilize its data products for education and public outreach purposes (EPO). Members of the PS1SC have recently completed some extremely successful work with the International Astronomical Search Collaboration to allow high school students in Germany, Texas, and Hawaii an opportunity to use images collected by PS1 to make asteroid discoveries. This first “pilot project” of 10 schools will be expanded to about 30 schools in a second “campaign” to be conducted during Spring 2011, and eventually the expansion could reach several hundred or even a thousand schools (thousands of students). And because of the vast amount of data produced by the wide field PS1 images, it requires only a handful of images to support such a large number of schools. For me the most gratifying part of bringing asteroid searches into the classroom is the high enthusiasm expressed by both the students and their teachers for participating in this program.

For the past few months we have teamed up the Pan-STARRS 1 telescope, designed to become one of the world’s most powerful asteroid hunters, with school students from the USA and Germany to discover and study asteroids – clumps of rock, between a couple and a few hundred kilometers in size, that cruise through our Solar System. At the close of the campaign, which was coordinated by the International Astronomical Search Collaboration, the students can look back on exciting eight weeks of asteroid search, which included the confirmation of four “Near-Earth Objects” (asteroids passing relatively close to Earth) and the discovery of what could turn out to be more than 170 previously undiscovered asteroids.

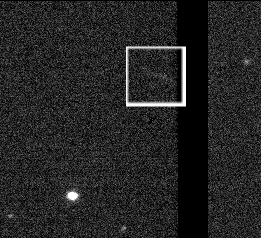

Asteroid 2010 UR7, confirmed as a Near Earth Object by students at Gymnasium Neckargemünd near Heidelberg. The object is indicated by the white box and appears as a faint streak as it moves through the solar system so fast it is blurred out in even a 40s image! Credit: PS1SC

As the 1.8 meter (71-inch) Pan-STARRS 1 telescope (PS1), one of the most powerful current survey telescopes, scans the night sky, its 1400 Megapixel digital camera takes more than 500 exposures per night. Between October 25 and December 21, 2010, a small fraction of these data found its way into classrooms in the USA and in Germany, where high-school students have used it to track known asteroids, and also to discover candidate objects that could be previously unknown asteroids. When Hawaiian skies were overcast, schools also received data taken with a telescope operated by the Astronomical Research Institute (ARI) in Westfield, Illinois.

Over the Internet, the participating schools received series of astronomical images. Each series included images of one specific region of the sky, taken an hour apart. During this hour, the image of a main belt asteroid (one lying between Mars and Jupiter) would have moved noticeably (in the images in question: about 100 pixels) relative to the distant background stars. The students examined the images for exactly this kind of position change, carefully sorting image artifacts from moving celestial objects, and reported back to the International Astronomical Search Collaboration, whose volunteers then checked the results and arranged for follow-up observations.

Some of the most interesting student observations during the project concerned “Near-Earth Objects” (NEO), asteroids or similar objects whose orbits bring them into the inner Solar System. Some NEOs might turn out to be potential “killer asteroids” that are bound to collide with our home planet; finding these is one main goal of the PS1 telescope. In order to keep track of NEOs, at least two separate observations at different times are required. Katharina Stöckler (age 17), an 11th grade student at Gymnasium Neckargemünd near Heidelberg, explains:

“We obtained a ‘NEO confirmation’ for the asteroid 2010 UR7 – the second observation ever made of that object, which confirmed the asteroid’s existence and gave crucial information about its orbit.”

Three additional such “NEO confirmations” were made during the project; in addition, 64 of the students’ observations amounted to the third or fourth time a specific NEO had been observed. All these observations provide important additional data to scientists studying the motion of NEOs.

In the course of the project, the students also observed 151 candidate objects in the Pan-STARRS data (plus an additional 20 candidates in the ARI/Westfield telescope data) that could be newly discovered main belt asteroids, which orbit the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. In one case, students from Benedikt Stattler Gymnasium, a high-school in Bavaria, Germany, discovered 7 such candidate objects in a single night! Before the students’ finds are confirmed as discoveries, however, and assigned provisional designation numbers, they will need to be observed again – for a number of the candidates, this is going to prove impossible; on the other hand, some are likely to turn out to have been previously known, after all. Once a newly found object has been observed over at least a whole orbit (which typically lasts 3 to 6 years), it is assigned a definite numerical identifier, and can also be given a proper name.

IASC director Dr. Patrick Miller, of Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas, says:

“Pan-STARRS images contain an amazing amount of data, providing students with opportunities for literally hundreds of new discoveries. With this amount of data, we could expand our campaign to a thousand schools a year, and tens of thousands of students, which is very exciting, and is an unbelievable opportunity for high schools and colleges!”

It is incredibly exciting that we can use a state-of-the-art system such as Pan-STARRS to allow students around the world to learn astronomy with real research quality images. We hope we’ve made this a valuable and enjoyable experience for both the students and their teachers. Hopefully this is only the first step in eventually involving as many as a thousand schools around the world.

If you’re interested in your school getting involved please email me at burgett AT ifa.hawaii.edu

More information can be found in this press release:

“Successful hunt for asteroids in the classroom”

Dr. Markus Pössel, Center for Astronomy Education and Outreach

Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy

The participating international teams of schools were:

1. Luitpold-Gymnasium, Munich, Germany

Ranger High School, Ranger, Texas

2. Christoph-Probst-Gymnasium, Munich, Germany

May High School, May, Texas

3. Benediktinergymnasium Ettal, Germany

Vernon High School, Vernon, Texas

4. Benedikt-Stattler-Gymnasium, Bad Kötzting, Germany

Bullard High School, Bullard, Texas

5. Werdenfels-Gymnasium, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Colleyville Heritage High School, Colleyville, Texas

6. St. Anna-Gymnasium, Munich, Germany

El Campo High School, El Campo, Texas

7. Helmholtz-Gymnasium, Heidelberg, Germany

Tarrant County College, Hurst, Texas

8. Gymnasium Neckargemünd, Neckargemünd, Germany

Brookhaven College, Farmers Branch, Texas

9. Lessing-Gymnasium, Lampertheim, Germany

Madisonville High School, Madisonville, Texas, and Baldwin High School, Wailuku, Hawaii

10. Life Science Lab, Heidelberg, Germany

Collin County College, Plano, Texas