Mapping Maui’s skys

March 31st, 2011 by nialldeaconCharting the heavens has always been one of the prime motivations of astronomy. However once larger telescopes began to be developed in the early twentieth century, the need for large continuous surveys of the sky to provide targets for these instruments became apparent. This need was filled by the telescopes invented by Bernhard Schmidt, an Estonian optician. Always an experimenter, Schmidt had lost his right-hand while playing with explosives as a child. His telescope combined lenses and mirrors to give sharp images over a wide field of view. Telescopes based on this design in California, Australia and Chile surveyed the whole sky over the course of fifty years. These surveys covered the sky multiple times in many different coloured filters. The frequent surveying of the sky led to the first classification system for exploding stars called supernovae and the discovery of thousands of nearby stars moving slowly across the sky.

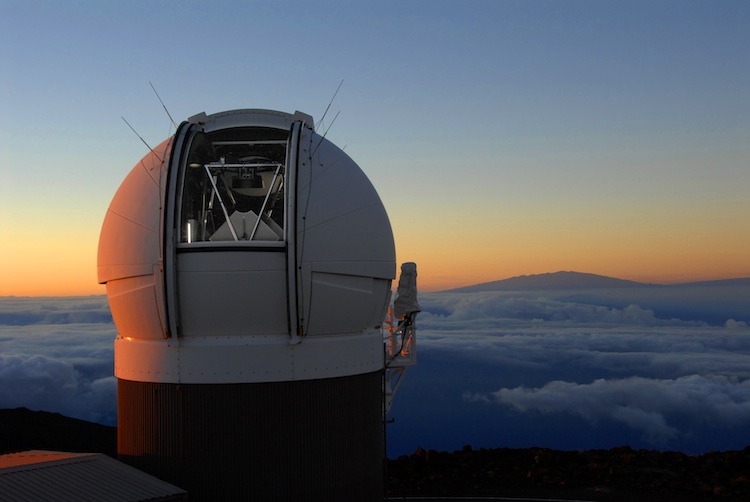

The PS1 Observatory on Haleakala. Photo Credit: Rob Ratkowski, PS1SC

This frequent surveying of the sky is one of the primary aims of the Pan-STARRS1 3Pi survey which gets it’s name from the area it covers. A steradian is a measurement of angular area and full sky is four pi steradians, but almost a quarter of that is not visible from Haleakala where PS1 is based. Hence by mapping almost all the sky over Maui, Pan-STARRS1 will cover three quarters of the sky, three pi steradians. The survey will be done in five colour filters named g, r, i, z and y. Three of these g (roughly green light), r (red light) and i (almost into the infrared) cover wavelengths visible to the human eye. The z and y filters (which like many things in astronomy, have names which don’t make much sense) cover far-red light mostly invisible to humans. Each of these are planned to be observed on up to six separate nights over three years. This mapping will be done forty times faster than the photographic plate based Schmidt telescopes.

Each of the six nights of observation per filter will consist of two images, half an hour apart. This interval will allow asteroids (including some that pass close to the Earth) which move quickly across the sky to be identified. In between nights more distant icy bodies can be identified by their celestial motions. Finally over a timescale of months and years nearby faint stars can be found, again by their movements on the sky. It’s not just varying positions which can be found by the survey, objects can change brightness too. Young stars sucking matter from disks of material around them can have leaps in brightness. Exploding stars can also be detected by their sudden changes in luminosity

Finally all the observations from the PS1 survey will be combined to make one deep multi-colour image of three quarters of the sky. This can be used to probe deeper both within and outside our Galaxy. It can peer into the depths looking at how galaxies are distributed in space, probing the mysterious dark matter which makes up nearly a quarter of our universe. It is also planned to use these images to look for subtle warping in the images of galaxies which are imprinted with clues about the strange dark energy which appears to drive the expansion of the universe.

You would think all this would be enough for one telescope, but PS1 is also undertaking a series of smaller surveys. Watch this space for more details.